Managing containers in cloud environments would be a lot simpler if there were just one type of container you and your staff needed to deal with. Any technology as multifaceted as containerization comes with a bucket full of new management challenges. The key is to get ahead of the potential pitfalls before you find yourself hip deep in them.

The simplest container scenario is packaging and distributing an existing application as a Docker container: all of the app’s dependencies are wrapped into a Docker image, and a single text file (Docker file) is added to explain how to create the image. Then each server can run only that instance of the container, just as the server would run one instance of the app itself.

Monitoring these simple containers is the same as monitoring the server, according to TechTarget’s Alastair Cooke in an April 2017 article. The app’s use of processes and resources can be viewed on the server. There’s no need to confirm that the server has all the required components because they’re all encapsulated in the Docker image and controlled by the Docker file, including the proper Java version and Python libraries.

How containers alter server management tasks

Placing apps in a Docker container means you no longer have to update and patch Java on the server. Instead, you update the Docker file and build a new Docker image. In fact, you may not need to install Java on the server at all. You’ll have to scan the Docker files for vulnerabilities and unsupported components in the image. You may also need to set and enforce policies relating to the maximum age of Docker images because dependency versions are set inside the image and can only be updated by creating a new image.

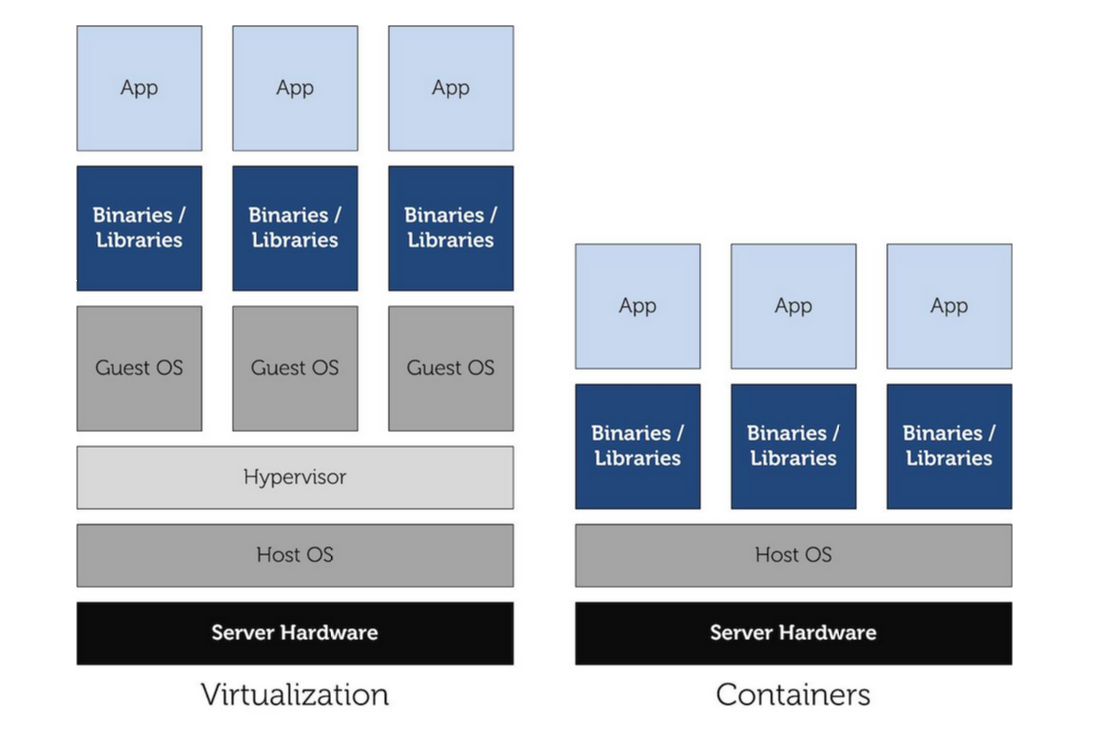

By removing a layer of software from the standard virtualization model, containers promise performance increases of 10 percent to 20 percent. Source: Conetix

Containers can be started and stopped in a fraction of a second, making them a lot faster than VMs. Microservice-enabled apps will use far more containers, most of which have short lifespans. Each of the app’s microservices will have its own Docker image that the microservice can scale up or down by creating or stopping containers. Standard server-monitoring tools aren’t designed for managing such a fast-changing, dynamic environment.

A new type of monitor is necessary that keeps pace with these quick-change containers. A solution being adopted by a growing number of companies is the Morpheus cloud application management platform. Morpheus’s instance catalog includes basic containers and VMs as well as custom services for SQL and NoSQL databases, cache stores, message busses, web servers, and full-fledged applications.

Morpheus support steps you through the process of adding a Docker host to any cloud via the intuitive Morpheus interface. Under Hosts on the main Infrastructure screen, choose one of nine Host types from the drop-down menu, select a Group, add basic information about the host in the resulting dialog box, set your Host options, and add Automation Workflows (optional), Once the Container Host is saved, it will start provisioning and will be ready for containers.

Provisioning Container Hosts via the Morpheus cloud app management service is as simple as entering a handful of data in a short series of dialog boxes. Source: Morpheus

Overcoming obstacles to container portability

Since your applications rely on data that lives outside the container, you need to make arrangements for storage. The most common form is local storage on a container cluster and addition of a storage plug-in to each container image. For public cloud storage, AWS and Azure use different storage services.

TechTarget’s Kurt Marko explains in an April 2017 article that Google Cloud’s Kubernetes cluster manager offers more flexibility than Azure or AWS in terms of sharing and persistence after a container restarts. The shortcoming of all three services is that they limit persistent data to only one platform, which complicates application portability.

Another weakness of cloud container storage is inconsistent security policies. Applying and enforcing security and access rules across platforms is never easy. The foundation of container security is the user/group directory and the identity management system that you use to enforce access controls and usage policies.

Containers or VMs? The factors to consider

The difference between containers and VMs is where the virtualization occurs. VMs use a hypervisor to partition the server below the OS level, so VMs share only hardware. A container’s virtualization occurs at the OS level, so containers share the OS and some middleware. Running apps on VMs is more like running them on bare metal servers. Conversely, apps running on containers have to conform to a single software platform.

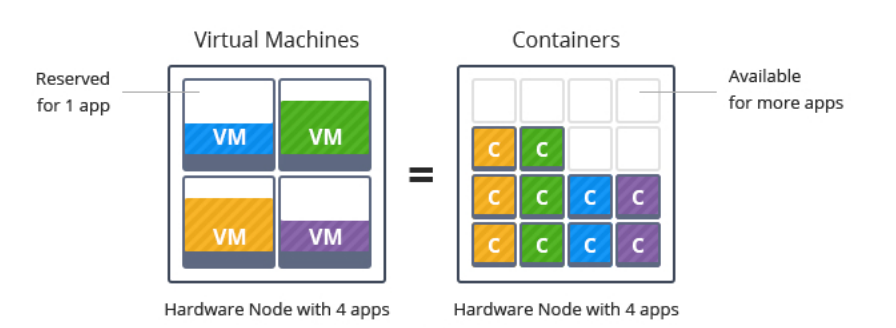

VMs offer the flexibility of bare metal servers, while containers optimize utilization by requiring fewer resources to be reserved. Source: Jelastic

On the other hand, containers have less overhead than VMs because there’s much less duplication of platform software as you deploy and redeploy your apps and components. Not only can you run more apps per server, containers let you deploy and redeploy faster than you can with VMs.

TechTarget‘s Tom Nolle highlights a shortcoming of containers in hybrid and public clouds: co-hosting. It is considered best practice when deploying an application in containers to co-host all of the app’s components to speed up network connections. However, co-hosting makes it more difficult to manage cloud bursting and failover to public cloud resources, which are two common scenarios for hybrid clouds.

Cloud management platforms such as Morpheus show the eroding distinctions between containers and VMs in terms of monitoring in mixed-cloud environments. It will likely take longer to bridge the differences between containers and VMs relating to security and compliance, according to Nolle.