It’s getting easier and easier for criminals to infiltrate your company’s network and help themselves to your financial and other sensitive information, and that of your customers. There’s a ready market for stolen certificates that make malware look legitimate to antivirus software and other security systems.

The crooks even place orders for stolen account information: One person is shopping for purloined Xbox, GameStop, iTunes, and Target accounts; another is interested only in accounts belonging to Canadian financial institutions. Each stolen record costs from $4 to $10, on average, and customers must buy at least $100 worth of these hijacked accounts. Many of the transactions specify rubles (hint, hint).

Loucif Kharouni, Senior Threat Researcher for security service Damballa, writes in a September 21, 2015, post that the cybercrime economy is thriving on the so-called Darknet, or Dark Web. Criminals now offer cybercrime-as-a-service, allowing anyone with an evil inclination to order up a malware attack, made to order — no tech experience required.

Sadly, thieves aren’t the only criminals profiting from the Darknet. Human traffickers, child pornographers, even murderers are taking advantage of the Internet to commit their heinous crimes, as Dark Reading’s Sara Peters reports in a September 16, 2015, article.

Peters cites a report by security firm Bat Blue Networks that claims there are between 200,000 and 400,000 sites on the Darknet. In addition to drug sales and other criminal activities, the sites are home to political dissidents, whistleblowers, and extremists of every description. It’s difficult to identify the servers hosting the sites because they are shrouded by virtual private networks and other forms of encryption, according to Bat Blue’s researchers.

Most people access the sites using The Onion Router (Tor) anonymizing network. That makes it nearly impossible for law enforcement to identify the criminals operating on the networks, let alone capture and prosecute them. In fact, Bat Blue claims “nation-states” are abetting the criminals, whether knowingly or unknowingly.

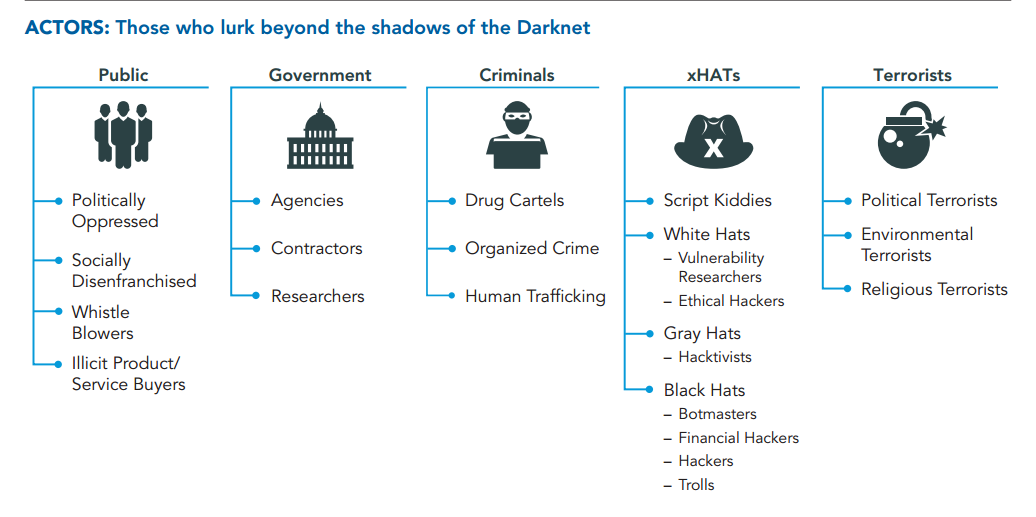

The Darknet is populated by everyone from public officials to religious extremists, for as wide a range of purposes. Source: Bat Blue Networks

While hundreds of thousands of sites comprise the Darknet, you won’t find them using the web’s Domain Name System. Instead, the sites communicate by delivering an anonymous service, called a “hidden service,” via updates to the Tor network. Rather than getting a domain from a registrar, the sites authenticate each other by using self-generated public/private key pair addresses.

The public key generates a 16-character hash that ends in .onion to serve as the address that accesses the hidden service. When the connection is established, keys are exchanged to create an encrypted communication channel. In a typical scenario, the user installs a Tor client and web server on a laptop, takes the laptop to a public WiFi access point (avoiding the cameras that are prevalent at many such locations), and uses that connection to register with the Tor network.

The Tor Project explains the six-step procedure for using a hidden service to link anonymously and securely via the Tor network:

In the fourth of the six steps required to establish a protected connection to the Tor network, Party B (Ann) sends an “introduce” message to one of the hidden service’s introduction points created by Party A (Bob). Source: Tor Project

Criminals cannot be allowed to operate unfettered in the dark shadows of the Internet. But you can’t arrest what you can’t spot. That’s why the first step in combatting Darknet crime is to shine a light on it. That’s one of the primary goals of the U.S. Defense Research Projects Agency’s Memex program, which Mark Stockley describes in a February 16, 2015, post on the Sophos Naked Security site.

Memex is intended to support domain-specific searches, as opposed to the broad, general scope of commercial search engines such as Google and Bing. Initially, it targets human trafficking and slavery, but its potential uses extend to the business realm, as Computerworld’s Katherine Noyes reports in a February 13, 2015, article.

For example, a company could use Memex to spot fraud attempts and vet potential partners. However, the ability to search for information that isn’t indexed by Google and other commercial search engines presents companies with a tremendous competitive advantage, according to analysts. After all, knowledge is power, and not just for the crooks running amok on the Darknet.