Marketing hype isn’t limited to the tech industries by any means, but the tech press certainly cranks up the hype machine to unprecedented levels. Among the recent darlings of the pundits is containerization.

A prime example of the container worshiping phenomenon is The VAR Guy’s Christopher Tozzi, who lists in an April 3, 2017, article all the ways that Docker saves companies money. From Tozzi’s description, you would think Docker can transform lead into gold: it’s simpler to maintain, it speeds up delivery of new software, it uses resources more efficiently, and to top it all off, Docker saves you money.

Quick, where do I sign?

It’s a good thing technology customers have a heightened sensitivity to such unadulterated claims of IT nirvana. A reality check reveals that no technology shift as fundamental as containerization is as simple, as fast, or as inexpensive as its backers claim it is. Yes, containers can be a boon to your data-management operations. No, you can’t realize the benefits of the technology without doing your due diligence.

Here are some tips for avoiding the pitfalls of implementing containers in multi-cloud and hybrid cloud environments.

Implementing containers on servers: Where are the bottlenecks?

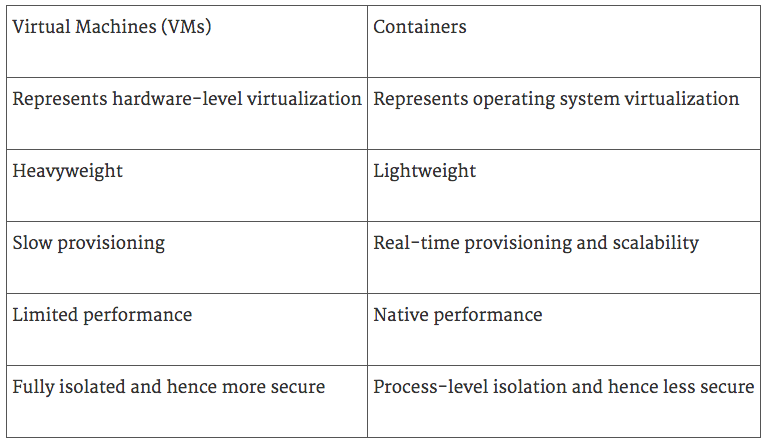

A primary advantage of containers over hypervisor-based virtualization is capacity utilization. Jim O’Reilly writes on TechTarget that because containers use the OS, tools, and other binaries of the server host, you can fit three times the number of containers on the server as VMs. As microservices are adopted more widely, the container capacity advantage over VMs will increase, according to O’Reilly.

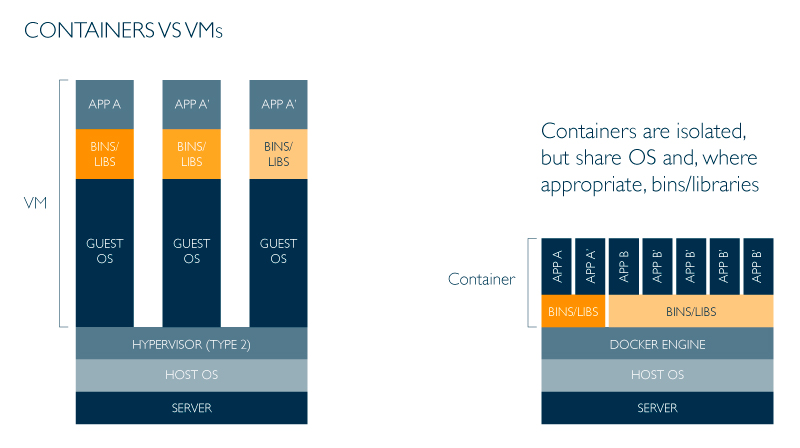

Containers achieve their light weight, compared to VMs, by doing without a guest OS. Instead, containers share an OS and applicable bins/libraries. Source: LeaseWeb

In addition, there is typically much less overhead with containers than with VMs, so containers’ effective load is actually closer to five times that of hypervisor-based virtualization. This has a negative effect on other system components, however. An example is the impact of the increased loads on CPU caches, which become much less efficient. Obviously, a bigger cache to address the higher volume usually means you have to use bigger servers.

Storage I/O and network connections also face increased demands to accommodate containers’ higher instance volumes. Non-volatile dual inline memory modules promise access speeds up to four times those of conventional solid-state drives. NVM Express SSDs have become the medium of choice for local primary storage rather than serial-attached SCSI or SATA. In addition to reducing CPU overhead, an NVMe can manage as many as 64,000 different queues at one time, so it can deliver data directly to containers no matter the number of instances they hold.

Distribute containers on demand among in-house servers or cloud VMs

The fact is, not many companies are ready to make another huge capital investment in big, next-gen servers with a cache layer for fast DRAM, serial connections, and 32GB of cache for each CPU, which is the recommended configuration for running containers on in-house servers. On the Docker Blog, Mike Coleman claims you can have it both ways: implement some container apps on bare metal servers, and others as VMs on cloud servers.

Rather than deciding the appropriate platform for your entire portfolio of applications, base the in-house/cloud decision on the attributes of the specific app: What will users need in terms of performance, scalability, security, reliability, cost, support, integration with other systems, and any number of other factors? Generally speaking, low latency apps do better in-house, while capacity optimization, mixed workloads, and disaster recovery favor virtualization.

VMs are typically heavier and slower than containers, but because they are fully isolated, VMs tend to be more secure than containers’ process level isolation. Source: Jaxenter

Other factors affecting the decision are the need to maximize existing investments in infrastructure, whether workloads can share kernels (multitenancy), reliance on APIs that bare metal servers don’t accommodate, and licensing costs (bare metal eliminates the need to buy hypervisor licenses, for example).

Amazon ECS enhances container support

A sign of the growing popularity of containers in virtual environments is the decision by Amazon Web Services to embed support for container networking in the EC2 Container Service (ECS). Michael Vizard explains in an April 19, 2017, article on SDxCentral that the new version of AWS’s networking software can be attached directly to any container. This allows both stateless and stateful applications to be deployed at scale, according to Amazon ECS general manager Deepak Singh.

The new ECS software will be exposed as an AWS Task that can be invoked to link multiple containers automatically. Any virtual network associated with the container is removed when the container disappears. Singh says AWS sees no need to make containers available on bare metal servers because there are better options for organizations concerned about container performance: graphical processing units, and field programmable gate arrays.

For many IT operations, going all-in with containers running on bare metal servers may be tomorrow’s ideal, but VMs are today’s reality as the only viable alternative for hybrid and public clouds. Enterprises typically run multiple Linux distributions and a mix of Windows Server and Linux OSes. It follows that to optimize workloads in such mixed environments, you’ll run some containers on bare metal and others in VMs.

According to Docker technical evangelist, Mike Coleman, licensing schemes tailored to virtualization make VMs more affordable, as TechTarget‘s Beth Pariseau reports. Coleman points out that companies nearly always begin using containers in a small way and wind up using them in a big way.